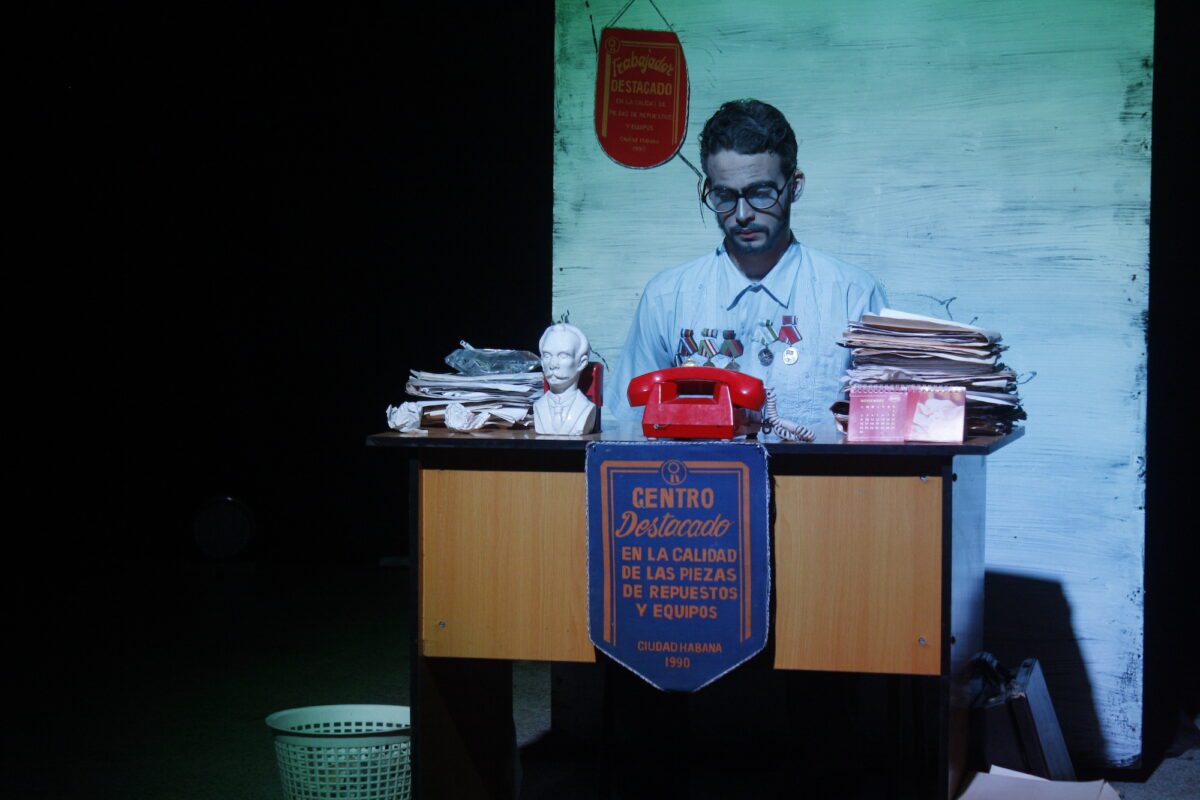

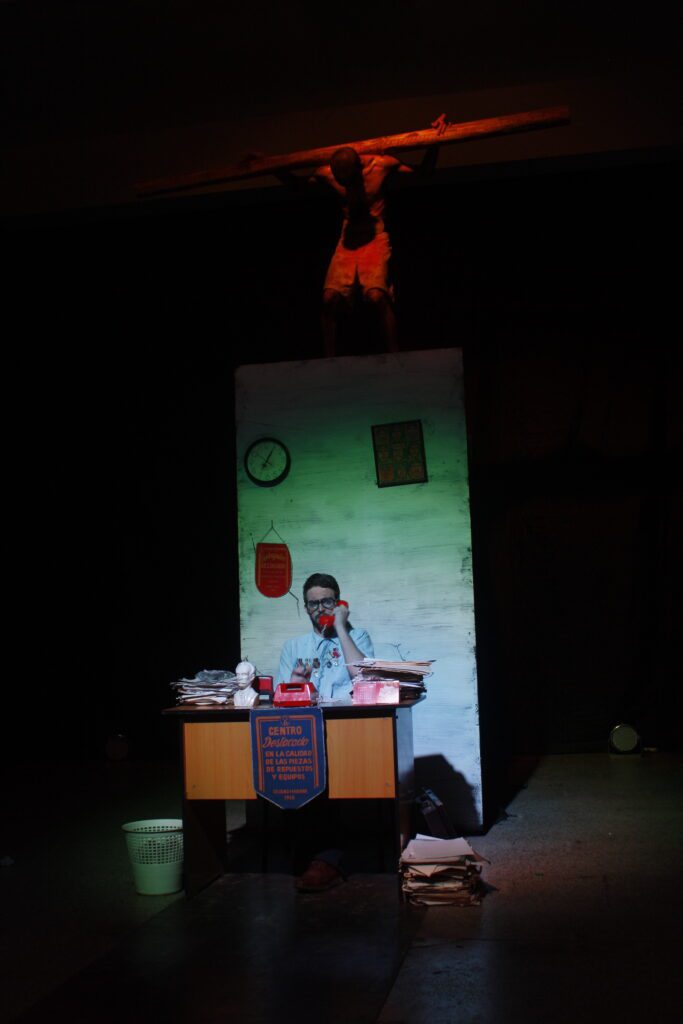

For Cuban-born theatremaker Arnaldo Galbán, translation is more than a linguistic exercise. Through Galbán’s translation project titled The Other’s, a platform dedicated to amplifying the voices of playwrights exiled or silenced under authoritarian regimes. The initiative debuts with a staged reading of ASCO (Disgust) by celebrated Cuban playwright Yunior García, bringing to English-speaking audiences a story shaped by the contradictions, complexities, and censorship of life in Cuba. Through translation, Galbán invites American audiences into the “cultural backpack” he carries — an offering of traditions, histories, and lived realities from beyond the U.S. — and calls for solidarity with artists worldwide whose work is threatened by repression.

Eva Wu: How did ASCO first find its way to you and the project, The Other’s?

Arnaldo Galbán: I met Yunior García a couple of years ago when we were both still living in Cuba. He was leading a civil movement that was gaining national and international visibility, and I was impressed by his values and talent. He’s also an actor and director, and I’ve always found his plays emotionally deep yet easy to speak.

When he was forced into exile — and months later, I also decided to leave Cuba to escape the difficulties I was encountering in my work — I came to the USA and started re-reading Cuban plays, looking for material I wanted to share with American audiences. I wanted work that could complete the idea so many people have about Cuba and Cubans. We are more than beaches, good dancers, and good lovers.

The first time I read ASCO, I was completely fascinated by its plot, its themes, and the rawness and depth of its characters. I reached out to Yunior and asked for permission to translate the play. After receiving a grant from LMCC and the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, I realized there are people out there willing to support this kind of work. That’s when The Other’s was born.

EW: Is The Other’s focused on Spanish-to-English translation, or is it about translation as a broader phenomenon?

AG: My dream for The Other’s is to find other immigrant artists who want to share the richness of their homeland’s arts. I’m based in NYC, and the audience I have the privilege — and the duty — to speak to is an American audience, in English.

What inspires me to translate into English is the understanding that America needs diversity of points of view. Americans need to realize that diversity is rich, powerful, and positive. We don’t arrive here empty-handed — we come carrying what I like to call a “cultural backpack” full of traditions, experiences, and the art of our people.

I translate to share, but also to show off. It’s about being proud of who I am and where I come from. And since American culture penetrates everywhere, influencing people across the planet, I think it’s time we “return the favor.” Here we are — this is what I lived before, this is what I have to share, what I’m bringing to the table.

EW: What were the most difficult nuances to translate in García’s work for an American audience?

AG: I spent a lot of time finding the right words, and I was lucky to have many American friends who proofread different versions. Finding the words was actually the easy part. Giving context was the challenge.

Understanding life in Cuba isn’t simple — it’s full of contradictions. “Schools and hospitals are free.” Yes, but we also have no food. “Art and museums are free or cheap.” Yes, but the same government that allows that also censors artists who challenge the status quo and imprisons people for their political ideas.

We had to add new lines to the English version to help people understand the situation. The hardest part was finding what to say in a way that gave context without breaking the rhythm of the scene or slowing the action.

EW: In a theatre ecosystem rich with immigrant playwrights working in English, why anchor your mission in translation rather than original English-language immigrant narratives?

AG: I love and support fellow immigrants creating in English. Most of the time, those works explore what it means to be an immigrant in America, which is necessary and urgent. But translation offers something different.

When you translate, despite what inevitably gets lost, it’s like inviting someone into your home, into the heart of who you are. It allows for a deeper understanding, one that goes beyond the immigrant experience in America to the lived realities in our countries of origin.

EW: Do you see translation as a political act?

AG: Absolutely. For me, it’s an act of resistance. As a Cuban artist who spent 27 years living on the island, I feel a responsibility to share what’s happening there. I have friends in Cuba trying to create while being suffocated by the government. They’re not strangers — they are people I know and love. I hope to find others from countries where authoritarian regimes try to destroy self-expression — artists who share my passion and want to join me in giving those voices a platform.

EW: In your research or personal experience, what are some of the less visible ways playwrights are censored, both in Cuba and elsewhere?

AG: In Cuba, everything is controlled by the government. Without government approval, you won’t get produced or published.

Now, with the internet, some writers send their work abroad and find recognition, but it’s still hard when you’re not allowed to share your art with your own people. They also try to isolate you, not just as an artist, but as a person. If you’re “uncomfortable,” they’ll make your life and the lives of those you love as difficult as possible.

If I were still living and creating in Cuba, it would mean everything to know that people outside cared about my life and my art. That solidarity would give me purpose.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.