Liu Shiming Art Gallery opened in March 2024 as a space dedicated to preserving and showcasing the work of Chinese sculptor Liu Shiming through thematic exhibitions. But what the gallery’s curatorial director Fran Kaufman really wanted to do is to present Liu’s body of work in context with other artists, to bring together what may seem as distant artistic visions and create a synergy based on related traditions.

Beijing Stories is the first contextualized exhibition at the gallery showing Liu Shiming’s work in conversation with another artist. The show establishes two perspectives on capturing and documenting the Chinese capital: Liu’s sculptures, created between the 1980s until his death in 2010, and the New York-based photographer Lois Conner’s panoramic photographs that she has been taking of the city since her first visit in 1984.

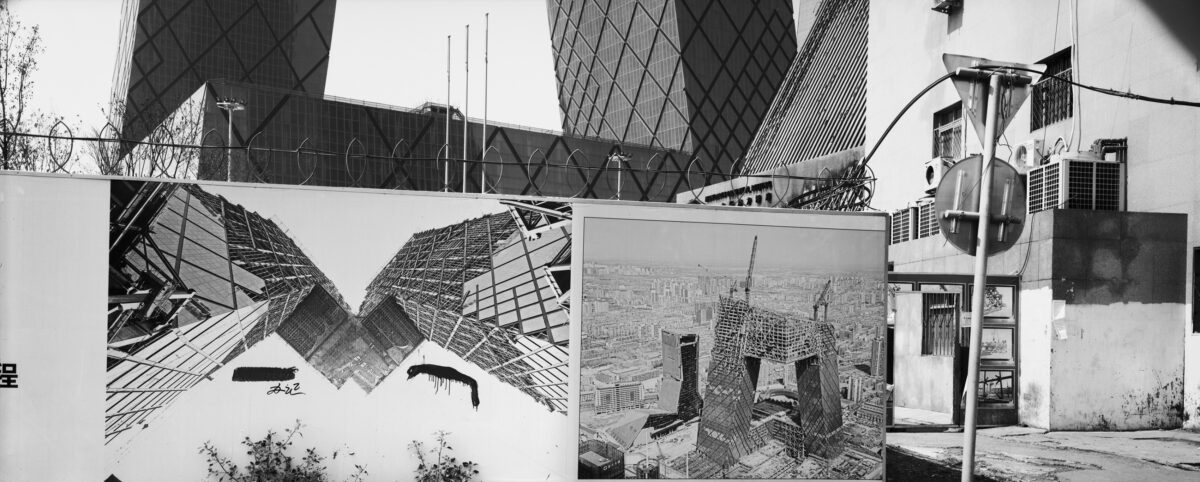

Through both practices, we see a city and society in constant flux, as Conner would describe. Liu’s sculptures represent everyday life and portray a generation that experienced one of the biggest political and cultural shifts of the last century. The exhibition includes pieces like Young Migrant Female Worker (1980), which presents the young female workers relocated to the city from the farms, showing them in a variety of poses as they adapt to their new environment; Hu Water (1983), where two bronze figures are shown in an agrarian moment engaged in manual irrigation; or Grandmother’s Pekingese Dogs (1988) where a woman, dressed in sleepers and holding her dog stands as a symbol of displacement. In juxtaposition, the photographs chosen from Conner’s work create a generational album of landscapes that presents the architectural growth and change of the place while showing how the city still preserves the character and culture of its older version.

MARIADO MARTÍNEZ PÉREZ: Let’s go back to the “beginning.” In 1984, you were awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship, and you went to China. Why China? What did you want to do there? What was the specific project you presented for the fellowship?

LOIS CONNER: We have to go far back, to 1979 [laughs]. When I was in graduate school studying photography, we had to take three elective classes. Among them, I decided to take “Chinese Landscape Painting in the Ming Dynasty.” There were maybe eight or nine people in that class. They all spoke fluent Chinese, they knew about the subject, and I had no idea. So, by the end of the first class, I asked the professor if I could drop it, but he said, “Absolutely not, we need somebody like you who will ask a different type of question.”

One of the stupid questions that I asked was about some pictures the professor showed us of these fantastical mountains and rivers; they were sort of green and gold, magical. They were karst formations. When the professor started talking about the long panoramic form of these mountains, it opened up a whole new world to me. I had never imagined a landscape like that. So I ended up applying to the Guggenheim Fellowship with the purpose of exploring the idea of panoramas inspired by the Yangshuo landscape.

MMP: So you had never visited China before this? How was that first time landing there?

LC: No, my only reference was that class. I felt curious about it. I had never been to Asia before. And China didn’t look anything like I imagined it would look like. Hong Kong was kind of what I had imagined mainland China to be, but the actual mainland China was very different. And I wasn’t disappointed. I’m interested in everything that comes from the land, the things that are built, and the things that have been taken away where you hardly see anything, but the sense of history is still there. And that was China.

MMP: And you’ve gone back, non-stop, during all these years. Why is China still a constant part of your work?

LC: When I left from my first trip, I didn’t know when I would be going back, but I knew I was not finished. And I still feel that way 40 years later. I mean, how much can you know of a civilization that has more than a 5,000-year history? I’m going to photograph a place where poets, painters, and writers have been going for millennia. You are never bored. If you were bored, you’d have to be insane because [China] is beautiful, raw, surprising, and never the same.

When I went to Beijing for the first time, no one knew that there was going to be this grand transformation. You respond to what is there, and then you realize that it’s in flux in a major way. You keep wanting to go back. I’ve spent a lot of time photographing Beijing. Even down the same street, with only six months in between, I’m surprised by how much it has changed. So you keep trying to figure places out, fall in love with the places, and want to go back again and again.

MMP: From the selection of photographs of Beijing in this show, could you tell me that “behind-the-scenes” story of one of them that was especially remarkable for you?

LC: When I talk about my work, I’m not interested in explaining it or telling why I think it’s important, but I’m always up for stories. There’s the story behind the photo of the National Stadium (under construction) before the 2008 Olympic games, for example. I went to that spot so many times, day and night, and I couldn’t get in because of the guards. But at some point, one of them told me: “You can come tomorrow to take the photograph. It’s my last night, and I’ll get you in.”

In the end, I went there and spent six hours. I can’t tell you how thrilled I was to be able to walk around the whole thing. Then the result was magical because you can’t tell its scale; there are no people to measure it with. There’s not a lot of activity at night, which also allows the darkness to reveal the structure in a different way.

MMP: You were capturing China through your lens at the very same time that Liu Shiming was capturing China through his hands. Did you know about his practice back then?

LC: You know what, no, I didn’t. I became familiar with his work through the exhibition. Fran (Kaufman) was looking for somebody who had photographed Beijing during this specific time period, and that’s when they contacted me.

MMP: And now, is there any piece from Liu that resonates with you?

LC: I have to spend more time with his work, looking at it and familiarizing myself with it. There are pieces I find very interesting, like the sensible mix of materials in these birds and their cage [says examining Looking at Each Other Through the Cage, 1990, where, according to the curatorial description, an unconfined sparrow gazes through the irregular bars of a birdcage at a smaller companion. Their wide spacing makes it clear that the caged bird is not physically trapped, highlighting the intangible nature of limitation]. I think there was a fantastic job with the show’s curation because you can see our connection.

MMP: Are you going back to take photographs again?

LC: I have a life in China now. I have friends there and things to do while I’m not photographing. I have been going there every year since the first time I went (I only skipped one year), and I’m going again in a few months. I’ll keep returning because I like creating things in response to the world, and China is in constant change.

The exploration of Beijing via the parallel practices of Lois Conner and Liu Shiming is on view at The Liu Shiming Art Gallery until March 21st.